I Learned Why His Name Was Irving

Jewish families' outside-the-box thinking in naming their baby boys.

It’s usually (almost always?) the case that after I publish an essay or article, I have some esprit de l’escalier second thoughts about something I could have said more elegantly, or a new information or ideas I thought of or were told about after the fact, and would have wanted to include.

Traditionally there’s been no recourse but now there is. Hence this launch of my series of Director’s Cuts: expanded versions of previously published pieces. I’m starting with a piece I published last week in The Forward.

(This is my third contribution to that publication, which I’m fond of for two reasons. First, my father and his family read it in the early years of the last century, from their homes on the Lower East Side and in Bushwick. Second, it helped my in my quest to write for publications that start with every letter of the alphabet. I was missing a “J” and stretched the rules a little but using the former name Jewish Daily Forward.)

My thought for this series is to reprint the original piece as published, then use footnotes—an idea I got from Nancy Friedman’s brilliant Substack Fritinancy, which you should all subscribe to—to discuss or amend. So readers can easily spot the footnotes, I’ve put the sentences before them in boldface.

This essay comes from a phenomenon I’ve been thinking about for years but had never seen any mention or commentary on. Then I started looking into it seriously and still didn’t see any mention of. If someone does find and show me a previous discussion, then I guess I’ll have to do a director’s cut of the director’s cut.

I LEARNED WHY HIS NAME WAS IRVING

My mother wasn’t a big one for jokes, but there was one she liked to tell. Years later, it showed up in the book Old Jews Telling Jokes, from which I quote:

A lady is taking her young son to his first day in school. She’s walking him to school and she starts giving him a little lecture.

She says, “Now, bubele, this is a marvelous thing for you, bubele. Bubele, you’re never gonna forget it. Just remember, bubele, to behave in school. Remember, bubele, anytime you want to speak, you raise your hand.”

They get to the school and she says, “Bubele, have a good day. I’ll be waiting for you when you get out of school.”

Four hours later, she’s standing there, and the little kid runs down the steps. She runs toward him and says, “Bubele, bubele, it’s been such an exciting day. Tell me, bubele, what did you learn today?”

“He says, “I learned my name was Irving.”

I, on the other hand, am a big one for wordplay. Years ago, I reviewed Margaret Drabble’s novel The Ice Age, which begins with an epigraph from a William Wordsworth poem, “London 1802”: “Milton, thou shouldst be living at this hour.” I opened the review by quoting the line and saying it was “not, as you might expect, the plaint of a Miami Beach widow.”

The humor in both cases, such as it was, rested on “Irving” and “Milton” being stereotypical American Jewish names. The stereotype is accurate. It is easy to think of examples (Irving Berlin, Irving “Swifty” Lazar; Milton Berle, Milton Friedman), and there’s also data to back it up.1 In a 2016 MIT study, researchers ingeniously culled data from Jewish U.S. soldiers in World War II (median birth date: 1917) and found that Irving was the single most common given name; Milton was 13th. Those scholars, and others, have briefly commented on the popularity of those two names and some others that made the top-thirty list for Jewish G.I.s: Sidney, Morris, Stanley, Murray, and Seymour.

But the comments have missed an important point about the phenomenon, which I call “My name is Irving” (MNII). It even slipped by the late Harvard sociologist Stanley (emphasis added) Lieberson, who wrote frequently and perceptively about the factors that go into parents’ naming decisions. In his 2000 book A Matter of Taste: How Names, Fashions, and Culture Change, Lieberson mentioned his own first name, plus Irving and Seymour, and described them as attractive to Jewish parents because they were “names that [were]… popular with fellow Americans.”

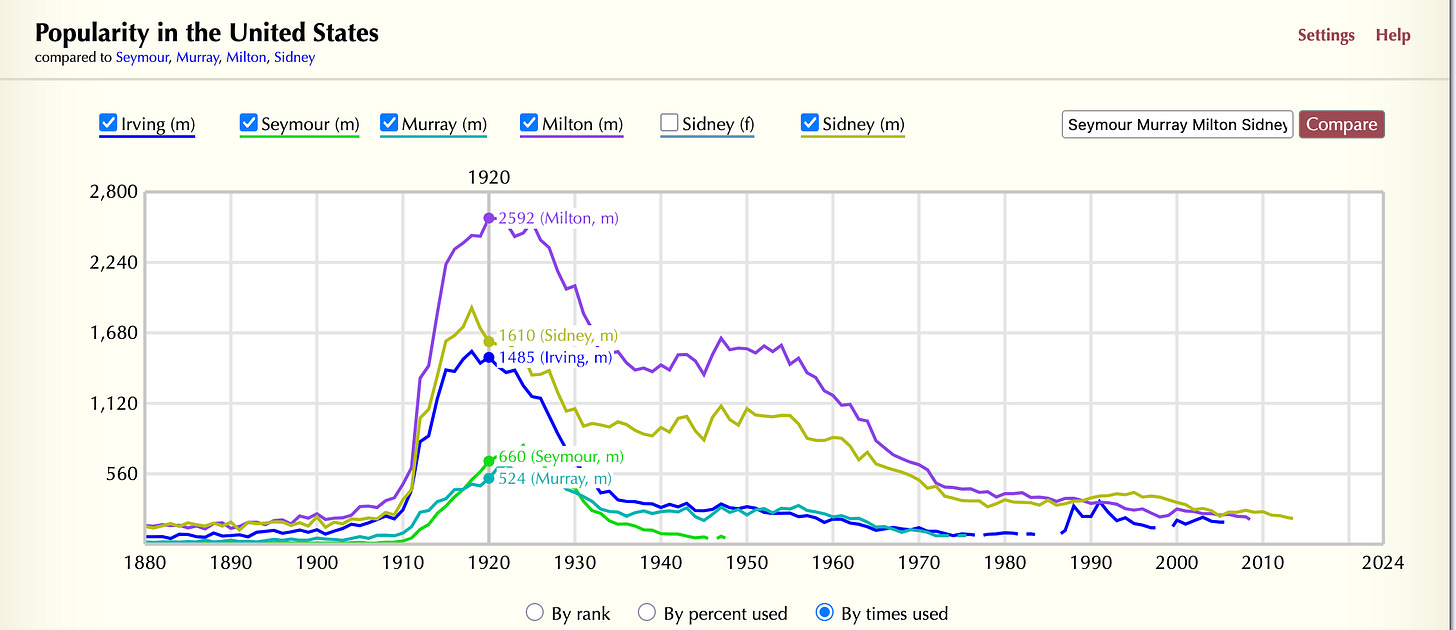

That isn’t really true. As the MIT study says, MNII names “stand out as favored by the Jewish immigrants but not by the general population.” According to Social Security Records, Irving was the 106th most popular name for all boys born in 1917, Milton the 75th; Stanley did a bit better at number 34.2 The others listed above are similarly low in the general count, especially Murray (241) and Seymour (242).

Someone else who has written widely in the field, Warren Blatt, called “Irving, Morris, Sidney, Sheldon, etc. … Anglo-Saxon names that were popular 100 years ago.”

That moves the discussion in the right direction but is misleading, because the word “popular” implies that they were traditional first names. In fact, Irving, Milton, Sidney, Morris, Stanley, Murray, and Seymour are venerable upper-crust British surnames. Only two of them are even mentioned in The Oxford Dictionary of English Christian Names (1947), Sidney and Stanley; the book notes that the latter’s “use as a christian name is apparently a recent development, originally due to the popularity of the explorer Henry Stanley (1841-1904).”

I hasten to say that Blatt was correct about other names in the G.I. top 30, such as William, Robert, Harry, Bernard, George, Harold, and Arthur.3 And his point does hold for girls. I think of my mother (Harriet) and my aunts Fay, Florence, Sylvia, and Estelle; we didn’t have a Sophie in our family, but many others did. All born roughly between 1905 and 1920, all given posh British names.

The last-name-to-first-name trend—which I’m not aware of having previously been discussed—hit quickly. Among the ten most common boys’ names for native-born members of Yiddish-speaking American households (that is, kids) in the 1910 census, there’s only one of the MNII type (Morris, at number seven). The others, in order, are Samuel, Louis, Harry, Jacob, Abraham, Isadore, Max, Benjamin, and Joseph.

What caused MNII to hit so soon after that? It’s impossible to say for sure, but it was not trivial. As Lieberson and a coauthor once observed, looking at first-name choices offers “a rare opportunity to study tastes in an exceptionally rigorous way.” I imagine the trend originated with some culture-loving Jews, who had been in the new country for a decade or more, who may have read Paradise Lost or seen Sir Henry Irving or one of his many thespian relatives on the stage, and thought such a distinguished name would cast a shimmering reflection on their sons.4 (And remember that they had a hall pass to use range freely in their choices because of the custom of giving kids a Hebrew or Yiddish names as well). Peers agreed, and soon the trend was viral.

MNII dissipated as quickly as hit, in some ways a victim of its own success. That is, it’s not necessarily attractive to give your kid a stereotypical name. There aren’t handy charts for later Jewish names along the lines of the World War II survey, but Social Security data for the whole country shows the MNII names peaking in popularity in the late teens and early ‘20s, then cratering.

In the 1930s and ‘40s, there were a lot of Normans, Henrys, Daniels, Jerrys, Howards, and Philips; and the popular ‘50s Jewish boys’ listed by Warren Blatt names rings true for my mischpoche: Alan, Andrew, Barry, Bruce, Eric, Jay, Marc, Michael, Peter, Richard, Robert, Roger, Scott, Steven, and Stuart. After that it was, and has been, back to the future, what with the flood of Noahs, Seths, Joshes, Sams, Bens, Isaacs, Abes, Maxes, and Jakes.

While Irving is a lost cause (it fell out of the top 1000 boys’ names in 2005, according to Social Security), MNII has a legacy: it arguably popularized the giving of last names as first names, which, judging from the current generation of young adults, is stronger than ever. Just ask Taylor Swift, Madison Cunningham, and consensus NBA Rookie of the Year Cooper Flagg.5

A Forwatd reader emailed me,“I feel qualified to comment on Ben Yagoda’s article because the name on my birth certificate is Irving and the name on my younger brother’s birth certificate is Stanley.”

The writer of the email, Irving Cohen, later in life changed his name to Israel—reversing the transition of the great songwriter Irving Berlin. He was born Israel Baline in Russia in 1888, came to America at the age of 5, and embarked on a songwriting career while still a teenager. His first published song, “Marie from Sunny Italy,” bore the credit “I. Berlin.” He legally changed his name to Irving Berlin in 1911.

It follows that some small number of American gentile babies were being given some of these names, one example being the literary critic Irving Babbitt, born 1865.

Some other popular Jewish boys’ names of the period didn’t make the G.I. top thirty but are also of the British-surname type. Blatt mentions Sheldon. I would add Jerome, Harvey, Marvin, Melvin, and Morton. The thing that was missing—and would be for several decades—were first names with an overtly Christian or New Testament tinge, such as Paul, Peter, Christopher, John, and Matthew.

A Forward reader, Jesse Rosenberg, sent me an email shedding light on why Irving, in particular, might have been so popular. He wrote that his

“grandfather’s given name at birth was Israel. He came to America as a child, and in his teenage years was Izzy to his friends. After a few years on Canal Street in New York (more or less the southern border of the Lower East Side) his family moved north to East 15th St. close to ... Irving Place, named after the writer Washington Irving, whose 19th-century dwelling had been located there (it’s long gone). My grandfather’s family’s home was also close to Washington Irving High School, named after the same fellow. A school for girls by day, in the evenings it was a vocational school for boys. This was where my grandfather studied lettering and signmaking… Switching his name to Irving couldn’t have been a more logical choice, and I wonder how many Irvings originated in lower Manhattan.”

More insight came from a Forward editor, Rukhl Schaechter,::

“In the Ashkenazi Jewish tradition, a child is named after a deceased relative. Many Hebrew and Yiddish male names start with the letter “yud” (which sounds like the letter I or Y): Yitschak (Isaac), Yaakov (Jacob), Yehoshua (Joshua), Yehuda (Judah), Yosef (Joseph), and many others that don’t have English counterparts (Yekhiel, Yerakhmiel, etc.).

“So when these parents chose a relative’s name that began with a “yud” they needed to find an English equivalen. … So they took what they considered to be contemporary American names beginning with the letter I — like Irving and Isadore.” Not to mention Irwin and Irvin.

And Jesse Rosenberg noted that not all of these names were given at birth: “a great many Irvings, Seymours, Miltons, Sidneys, Sherwins, etc. were anglicized adaptations intended to help people named Moshe, Mottl, and Saul to assimilate.”

As the astute Michael Sokolove pointed out to me, the beginning of Flagg’s season has been less than stellar. We’ll see how he looks at the end of the year.

I thank you, and my late Uncle Irving (né Israel) thanks you.

This was really interesting, thanks!

Pretty certain that Mike’s and my Uncle Irving was “Itche” in Yiddish (his first language ), or in Hebrew Itzchak (Isaac)